Introduction

Financial institutions today face the complex and critical task of understanding how climate change will affect companies, markets, and ultimately their portfolios. This challenge extends beyond simply assessing which companies are “green” and which are not. It requires a deep understanding of how climate dynamics are reshaping business models, influencing capital allocation, and redefining long-term value creation. As the financial sector grapples with these new realities, two central questions have come to dominate investor thinking:

1. How are companies genuinely transitioning to a low-carbon economy?

2. How resilient are their business models to the multifaceted risks posed by climate change?

This article provides a structured framework for addressing these questions, integrating the latest data and research to offer a clearer path forward for investors, banks, and other financial stakeholders.

The Transition Imperative: From Ambition to Action

Investors and banks are increasingly focused on whether companies’ climate targets are credible and if their stated ambitions are being matched by tangible progress. This means moving beyond headline commitments to scrutinise actual performance against pledged goals. The credibility of a company's transition plan now rests on several key pillars:

- Historical Performance: A track record of emissions reductions, investment trends, and operational changes provides a baseline for assessing the feasibility of future targets.

- Target Granularity: Stakeholders now expect visibility into how targets are structured—broken down by business line, geography, technology, and even individual CapEx projects.

- Governance and Accountability: The integration of climate goals into corporate governance, from board oversight and management incentives plans, reveals whether these goals are aspirational or truly embedded in the company’s decision-making processes.

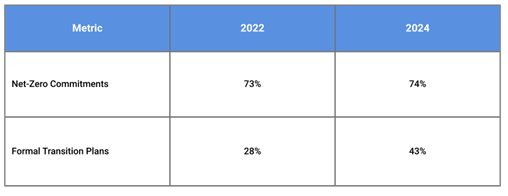

RMI’s recent analysis of the world's 100 largest financial institutions highlights a significant shift from making commitments to actively planning for the transition. While net-zero commitments have become the industry norm, the focus has now turned to the development and execution of formal transition plans. However, progress remains uneven across regions and the financial sector as a whole.

As the table above illustrates, while the growth in net-zero commitments has plateaued, the number of large institutions with formal transition plans has rapidly increased in just two years. This indicates that the industry is moving into a new phase of implementation, a trend that is further substantiated by the fact that 73% of the largest financial institutions now have disclosures that align with at least four of the five transition planning criteria set by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ).

Ultimately, this trend makes clear that financial institutions are starting to focus on bridging the gap between ambition and reality. Financial institutions require data-driven evidence that companies’ transition narratives are supported by concrete actions and measurable results, not just rhetoric.

The Climate Risk Landscape: A Tale of Two Risks

Understanding a company's exposure to climate-related risks is the second critical component of a comprehensive climate assessment. These risks are broadly categorised into two types: transition risks and physical risks.

Transition Risk: More Than Just Carbon Pricing

Transition risk is often narrowly and mistakenly associated with the imposition of aggressive climate policies, such as carbon pricing. In reality, transition risk encompasses a much broader set of factors related to the shift to a low-carbon economy. This includes technological disruptions, shifts in consumer preferences, and industrial policies that can reshape entire markets.

While carbon pricing is a significant factor, with revenues exceeding $100 billion in 2024 and covering 28% of global emissions, it is by no means the only, or even the most important, driver of transition risk. In fact, only 1% of global emissions are currently priced high enough for competitive markets to feasibly meet the temperature targets of the Paris Agreement, suggesting that other forces have a role to play.

For example, industrial policy, particularly in China, the UK, Germany and even the United States, has been a powerful driver of transition, reshaping global markets for solar panels and, more recently, electric vehicles, which accounted for 20% of global car sales in 2024, displacing over 1.3 million barrels of oil per day. This technological and market shift poses a significant transition risk to incumbent automotive manufacturers and the oil and gas industry, even in the absence of explicit carbon pricing policies.

Such dynamics highlight that transition risk is not a distant threat but a present-day reality that can significantly impact the valuations and financing costs of incumbent firms.

Physical Risk: The Tangible and Growing Threat

In contrast to the often-misunderstood nature of transition risk, physical risks are becoming increasingly tangible, and their financial impacts are more observable. These risks, which stem from extreme weather events (acute risks) and long-term shifts in climate patterns like rising sea levels and chronic heat stress (chronic risks), are already causing significant economic damage.

Physical risk models can provide a sense of the potential for future damage, but the real-world costs are already mounting. According to the Climate Policy Initiative, projected portfolio losses from physical climate risks could reach 5% globally under a +2°C to +3°C warming scenario. In emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), which are often more vulnerable to climate change, these projected losses escalate to between 10% and 15%. These figures underscore the material financial threat that physical risks pose to investment portfolios.

Physical risk is transition risk, in that the mounting costs of climate change will increase the difficulties faced by companies in transitioning industries. A typical example is a gas power company, whose power plants are vulnerable to water stress and wildfires. Forced outages or asset write-downs are further compounded by the disruptive impact of solar plus storage, which, on a cost basis, will provide reliable power at >30% lower cost. This is not mere pessimism; these are the actual power market dynamics occurring in California and around the world, according to the IEA.

While, intellectually, it’s important to identify and isolate the root cause, transition or physical risk. In practical applications, it all comes down to how these risks flow to a company’s bottom line. Recognising this interplay provides a natural entry point into a more holistic perspective on risk—one that emphasises how companies withstand and adapt to the full spectrum of climate impacts.

Integrating Risks: A New Definition of Resilience

We believe transition and physical risks should be seen as interconnected components of a broader concept: climate resilience. In this context, we define climate resilience as the stability of a company’s current and future earnings under the multifaceted impacts of climate change. Understanding this resilience requires stepping back from narrow ESG metrics and scores and focusing instead on the durability of a company’s core business model and its capacity to adapt and thrive.

Resilience in this context has two key dimensions:

- Risk Mitigation: This involves investing in measures that protect a company's existing earnings streams. The central question here is how margins can be squeezed or disrupted by physical or transition risks. Physical risks can directly impact operations through damage to assets, supply chain disruptions, or increased costs for cooling, heating, or water management. Transition risks can compress margins through rising carbon prices, shifts in consumer demand away from high-carbon products, or the need to write down stranded assets. The relevant metrics to consider are the company's current operating expenditure (OpEx) as well as its technology mix and how that will evolve under a base case scenario based on the company's current forecast. Understanding these margin pressures requires detailed analysis of cost structures, revenue dependencies, and exposure to climate-sensitive inputs or markets. Examples of mitigation strategies include adapting operations to withstand extreme weather events, diversifying supply chains to reduce vulnerability to physical or transition risk impacts, and hedging against carbon price volatility.

- Business Transformation: This dimension focuses on shifting toward new technologies and business models that can capture growth opportunities arising from the low-carbon transition or the increasing demand for resilience-building solutions. From a business transformation perspective, the key is ensuring that a company has sufficient capital expenditure (CapEx) plans to achieve its technology targets. This articulates well with the climate targets that companies set, such as achieving 50% electric vehicle production by 2030. Business transformation is where climate ambition truly comes into play, and where it becomes crucial to have a bottom-up view on whether companies will be able to achieve their stated goals. This could involve reallocating capital to green technologies, developing new products and services for a circular economy, or entering new markets created by climate adaptation needs.

While related, these two approaches are not identical. Risk mitigation is fundamentally about protecting existing value, whereas transformation is about creating new value. Both require significant capital expenditure and strategic foresight, and both are critical for ensuring long-term earnings durability in a climate-constrained world.

The Primacy of Cost of Capital and Earnings

However, a critical reality must be acknowledged: the cost of capital and earnings are everything. It does not matter how ambitious a company's climate plan is if its cost of capital suddenly increases or its earnings decline—in markets driven by short-term shareholder capitalism, the plan is much more likely to be abandoned. Therefore, financial institutions should stay away from relying solely on their clients' most ambitious targets, and instead consider how a company's transition plan affects its cost of capital and earnings. If the transition plan puts too much pressure on these two fundamental metrics, it is almost certain to be abandoned or significantly reshaped.

This is not mere cynicism but a self-evident recognition of corporate behavior and market dynamics. In the short term, CEOs often embrace ambitious climate commitments in favorable environments, but the actual delivery of these commitments may become the next management team's problem. The case of BP provides a stark illustration of this dynamic. After announcing ambitious plans to reduce oil and gas production and pivot toward renewables, the company subsequently scaled back these commitments in response to shareholder pressure and the need to maintain the competitive profitability and returns required to satisfy shareholders and raise new capital. This pattern underscores the importance of evaluating transition plans not just on their ambition, but on their financial viability and alignment with core business economics.

The Data Financial Institutions Truly Need

To accurately assess a company’s climate resilience, investors and banks need to move beyond simplistic ESG scores and reductive temperature alignment metrics. Data needs to not just show how companies are transitioning, but how those transitions impact their future profitability and risk exposure. This requires a deeper integration of operational and financial data to answer several key questions:

- Technology Switching and CapEx Alignment: How are companies reallocating production, capacity, and capital toward new, low-carbon technologies? What does this mean for their future earnings potential and stranded asset risk?

- Margin and Revenue Impacts: How are shifts in technology, policy, and consumer demand affecting profit margins? Combining price, cost, and revenue data can help quantify how these pressures may squeeze or expand profitability.

- Scenario-Based Resilience: How resilient are companies’ business models under a range of different policy, technology, and physical risk pathways? Stress-testing portfolios against credible climate scenarios is essential for understanding potential future losses and opportunities.

In short, financial institutions are seeking a data-driven, forward-looking view of climate resilience—one that connects transition plans, real-world performance, and financial outcomes. The most valuable metrics are those that are core to a company’s credibility and operational model. The focus should be on two key indicators:

- Ambition Delta: The degree to which a company’s future emissions and CapEx plans align—or fail to align—with its stated climate ambitions or scenario benchmark.

- In practice: A smaller delta indicates credible, executable transition plans, while a larger one highlights potential greenwashing or misallocated capital. The goal is not to have the greatest ambition, but a sustainable ambition with a small positive or negative delta with forecasted emissions.

- Impact Resilience: The extent to which a company’s future earnings, margins, and capital needs remain robust under different transition and physical risk scenarios.

- In practice: This metric assesses how effectively a firm’s business model can sustain profitability while maintaining consistent investment in decarbonisation. The key is demonstrating pragmatic balance-pursuing decarbonisation without undermining long-term financial viability, and vice versa.

By focusing on these core metrics, financial institutions can develop a more robust and defensible understanding of climate risk and opportunity, forcing a deeper engagement with the data and assumptions that underpin their investment decisions.

Conclusion

The financial sector is at a critical juncture. The transition to a low-carbon economy is no longer a distant prospect but a present and accelerating reality. As this analysis has shown, the landscape of climate risk is complex, encompassing not only the well-understood physical impacts of climate change but also the disruptive force of technological and policy-driven transitions. Financial institutions that continue to rely on outdated models and simplistic metrics will find themselves increasingly exposed to these risks.

By adopting a simple, data-driven framework centered on the concept of climate resilience, investors and banks can better navigate this challenging environment. This requires a granular assessment of companies’ transition plans, a clear-eyed view of their exposure to both transition and physical risks, and a forward-looking analysis of how these factors will impact long-term earnings. The institutions that succeed will be those that can effectively bridge the gap between climate ambition and financial reality, positioning themselves not only to mitigate risk but also to capture the significant opportunities of the coming transition.

Let's talk

Looking for more details on using our forward-looking asset-based data? Our team is here to support you.

Contact us